When I tell people that I'm a taphophile, someone who likes graveyards, I often get funny looks. When I write books like Desecration, that open with a murder in a museum of medical specimens, and explore themes of corpse art, body modification and teratology, people question my interest with such morbid things.

But if you understand these fascinations, if you are my kind of weird, then you will also love Morbid Anatomy, a fantastic blog that covers the themes I am passionate about and much more.

But if you understand these fascinations, if you are my kind of weird, then you will also love Morbid Anatomy, a fantastic blog that covers the themes I am passionate about and much more.

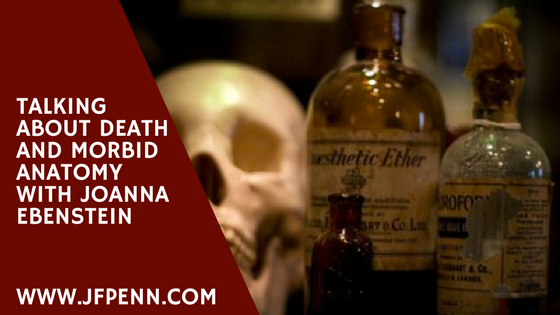

In the video below (or here on YouTube), I talk to Joanna Ebenstein, multidisciplinary artist, author and designer, as well as the founder of Morbid Anatomy blog and library and now the creative director of the Morbid Anatomy Museum in New York. You can read discussion notes below the video.

We discuss:

- Joanna's background in photography and graphic design, and how she got started with an exhibition on medical museums and anatomical art that led into a blog and then a global community of people interested in these darker topics

- The themes of Morbid Anatomy include 19th century hysteria, the uncanny, art and anatomy, death and culture, collectors and collecting, sexology, freaks and monsters, baroque art, gothic literature, history of medicine, taxidermy and there are now artefacts as well as books.

Things that fall through the cracks and flicker on edges, delightful in ways to certain kinds of minds.

- We discuss why some people find topics like death confronting, and about the lack of dignified discussion around death. There is an avoidance of great emotion in our society, but some of us are drawn to investigate these things that seem ‘wrong' or taboo in some way.

- On how two smiley, upbeat women can be into such dark things …

Some of the objects that Joanna is interested in, including Anatomical Venus figures (which I used in Desecration as a clue to the murder), as well as a small Korean funeral doll that would assist in the underworld.

- On the Morbid Anatomy anthology which is a collection of essays and full colour pictures that will please people interested in these type of topics. It includes essays on books bound in human skin, anthropomorphic taxidermy, 18th century anatomical models and so much more. The cheapest way to get it right now is to be part of the Kickstarter for the Museum here.

- The Morbid Anatomy Museum will be opening in New York this year, it is an extension of the Library that Joanna has been running privately and will contain lots of artifacts, books and exhibitions as well as community spaces. You can read about the plans and join the funding on Kickstarter here. I'm really excited about it!

You can find Joanna at the Morbid Anatomy blog here or @morbidanatomy on Twitter, as well as her gorgeous photos on Flickr.

Right image: Flickr Creative Commons Peter Pelisek

Transcript of full interview with Joanna Ebenstein

Joanna Penn: Hi, everyone, I’m thriller author J.F.Penn, and today I’m here with Joanna Ebenstein. Hi, Joanna!

Joanna Ebenstein: Hello!

Joanna Penn: Just as an introduction, Joanna is a multidisciplinary artist and author and designer, as well as the founder of Morbid Anatomy blog and the Library, and is also now the Creative Director of the Morbid Anatomy Museum in New York. So exciting!

So, Joanna, tell us a bit more about you and your background, as you seem to be just doing so much.

Joanna Ebenstein: Sure. There’s no easy way to explain what I do, I think. People ask, “Are you an artist?” – I don’t know what I do. I make things. So, I got into morbid anatomy actually as a total fluke. I was a photographer at the time, I was doing graphic design for a living, and I met this curator at a medical museum who invited me to do an exhibition about medical museum photographs that I’d already been collecting. So when I got that gig, I thought, “Well, if this is really going to be a proper exhibition, I should actually go back and re-shoot some of the stuff I’ve already shot, and go to all the museums that I think are the very best.”

So I did a lot of research, and I started to collect materials, and I ended up going on a one-month pilgrimage to what I consider to be the great medical museums of the Western world, so I went to La Specola in Florence, I went to Paris, I went to London, the Hunterian, I went to Edinburgh, I went to Vienna: I went all over the world, basically, and throughout the United States as well. And the blog to me was really just my way of starting to organize all the material I had collected. Before then there was not even a place where you could find all the links to medical museums. So I was using these links again and again in my research, and all of these online exhibitions about anatomical art, and then the books I began to collect through speaking to curators and getting deeper into the research, so I started a bibliography, and then I just started doing posts.

And it honestly never occurred to me that anybody would be interested in this besides me. I really didn’t: I know it sounds foolish now, but it was just something I did – it was like a process-based artwork in order to figure out what I really wanted to say about this incredibly rich stuff that was really, really hard to wrap my head around. And then, pretty much from the very beginning, I linked to three other blogs I liked in the world, and then they linked to me – I didn’t know how these things happened, but things snowball, as you know, very quickly on the Internet, and before I knew it, there was a following of people, and I was getting emails from people all over the world saying they had never known there was anybody in the world that was interested in this material either. So it was really, really a wonderful thing.

Joanna Penn: It’s fantastic. And for anybody who doesn’t know the blog, some people might not, tell us, because it’s not just medical specimens anymore, is it, a bit more about all the topics you cover.

Joanna Ebenstein: Basically, the blog has gotten to a point where I just write about anything that interests me. So when I think about the categories, I think about the Library. A couple years after I started the blog, I started the Morbid Anatomy Library, and when I look at the shelves and the division of shelves, that helps me kind of, again, understand what it is I’m interested in. So, here are some of the topics I would say you would find on shelves and on the blog: 19th century hysteria; the uncanny; art and anatomy; death and culture; collectors and collecting; sexology; freaks and monsters; art, baroque art in particular; gothic literature; history of medicine, broadly considered; and then we’ve also started to collect artifacts, so we have the books, we have the moulages, we have lots of taxidermy, books on taxidermy. How to explain that in a nutshell is difficult, and we’ve been struggling with that with the museum, but what I think works for me is these things that fall between the cracks, and also these things that flicker on edges, is how I would describe it. These things that are confusing in a delightful way to certain kinds of minds. I think certain minds don’t like that kind of confusion, but to me, things that flicker on the edge of categories I find thrilling, and I think all of the things I’m interested in flicker on the edge of categories.

Joanna Penn: Yeah, and I felt also like I was kind of coming home on your site. Whenever I go on there, I’m like, “Ooh, this is so cool, and this is awesome!” I stumbled upon it when I was researching my book, “Desecration,” which opens with a murder in the Hunterian, and has a lot about medical specimens and monsters, teratology and that kind of stuff. And I was just like, “Wow, this is so cool,” and I feel, I now say, you’re my kind of weird. The blog is my kind of weird, which is amazing. So why do you think some people feel uncomfortable about some of this stuff? Particularly, people say that the topics of my book, “Desecration,” confronting is the word that they use.

Why do you think that people struggle with these topics?

Joanna Ebenstein: I think there are a few reasons. I think first of all, I think right now, at least in American culture – I don’t know how much this is true of British culture –death is the white elephant in the room, it’s the thing that people are pretending not to see, and it expresses itself in certain ways: it can express itself in horror movies, or CSI TV shows, but there’s really no dignified discourse about it. And for example my whole life, I’ve been called morbid, which is why I called the blog Morbid Anatomy: I felt like I kind of wanted to reclaim this idea.

Because to me, for the longest time, I’ve thought, “OK, maybe I am morbid,” then I really began to think about it. And as I traveled through Europe for the first time and saw all of these fine art representations of death, it really blew my mind. I was 16, this is kind of the turning point for me, and growing up in California, where everything’s very laid-back and cool and optimistic, I was really drawn to images of things that weren’t optimistic. Even when I was a child, I really loved books in which the main character died, and, but I’d say it’s because those things elicit great emotion, a real emotion, and I don’t think, honestly: my new working theory is I don’t think people really want to feel great emotion. I think it’s confronting, these things can be called confronting, because they’re emotional: they kind of overcome our rational mind. And I’m kind of bored – I shouldn’t say I’m bored of the rational mind – but I don’t consider myself a rational being. I can be, and I have certain things that are rational, but I’m actually much more interested in things that are not rational. And I think that death is an important topic that’s not been dealt with.

And the other thing I would say, you know, going back to these things that flicker on the edges, I think what that really does is it challenges the very notion of how we think about the world, and the fact that humans are meaning-making machines that are imposing these meanings on things all the time, and these things that flicker challenge that. And I think there are certain people, creatives, perhaps, and maybe others, who find that thrilling because it’s a sense of possibility, and it’s just a delightful feeling, these things that are so confusing. For example, when I look at the Anatomical Venus, which is one of the central objects, as you know, from the Anatomical Theater, I see it flickers on so many edges to me. There’s life and death; there’s religion and, and medicine; there’s sex and edification, all of these things. And to me, when I follow those, when I try to examine that flickering and I think about why, I think, and my background is history, so that’s how I think about it, “At the time that this Venus was made, those divisions didn’t exist.” So our mind actually just doesn’t know how to deal with it. In the 18th century, no one was saying, “This is bizarre,” people were saying, “This is amazing, this is the proper way to teach anatomy, I’d like to take five for my museum.” Now we look at that and it seems wrong. And I’m very, very interested in these things that seem wrong to us, and what it says about us and how we’ve changed as a people. Particularly how, when it’s about death. Because I think death has become this exoticized other that we’re very uncomfortable with, and any time death butts up against beauty, or intrigue, or pleasure, it seems taboo, and really, it flickers on that edge that makes some people uncomfortable and thrills others, if that makes sense.

Joanna Penn: That’s great, and I’m really happy now, because I’ve been struggling with my branding for my fiction, and I’ve now settled on “Thrillers on the edge.”

Joanna Ebenstein: That’s funny, that’s flickering on the edge!

Joanna Penn: So I’m really excited, because I feel that; I feel like I want to always be on the edge of what’s kind of slightly unacceptable.

But it’s interesting, like you said, people call you morbid, and people have always called me an ‘old soul’: do you get that?

Joanna Ebenstein: Yeah, I get that, too, as well, when I’m not getting morbid. It depends. I mean, the answer’s yes.

Joanna Penn: My follow-up question is, the other thing I get is “Oh, but you look like such a nice, normal person, and you’re so happy and upbeat, how can you write about such dark things, why don’t you write about happy things?” What, what do you say when people say that to you?

Joanna Ebenstein: Well, to be honest, people often don’t say it to my face! I read it in my press. No one ever says that to me, but often that will be the lead for an article, they’ll really emphasize that I’m blonde, and smiley. Nobody says it to me. I think people ask me a lot of questions, but it’s not exactly that. You know, they’re curious why I’m interested, and they try to get at it in an oblique way. People don’t say it to me in so many words. I don’t know what I would say in return. I mean, I think I’d say what I’m saying to you, which is, I can’t imagine why anybody wouldn’t think about death. To me, the idea that you wouldn’t be concerned with death or really think about it, it’s the greatest human mystery of all. Everybody dies, everyone who’s lived has died, we have no idea what it is. And it defines our life: our relationship to that defines our time on Earth, as long as we have a limited time on Earth. So, to me, it’s the most profound and interesting and intriguing and worthy of thought thing I can imagine. And I think there’s something really – honestly – morbid about not thinking about it.

And that’s kind of what this project is trying to say, by showing this preponderance of historical iterations of people dealing with death in various ways, that all look bizarre to us today, because we have none. I’m hoping on one level, this is one thing the project, I would like it to do, is make people just think, “Well, that’s interesting, why does this seem so bizarre to me, why, why am I in a room surrounded by paintings and photographs and moulages and all these things that deal with death and beauty in various ways, and they all seem utterly bizarre to us today.”

Joanna Penn: I mean, the objects are all really cool, and I used an Anatomical Venus in my story as a clue.

Joanna Ebenstein: Oh, that’s excellent!

Joanna Penn: Which was kind of the basis of it. And you’re right, in England and in Europe we have a lot more of these objects just hanging around.

And I wondered, what are a couple of the really cool things that you have that still kind of delight you, or things that you’re craving that you’d love to get hold of?

Joanna Ebenstein: Well, the thing that I’m craving that I’d love to get ahold of is an Anatomical Venus.

Joanna Penn: OK, but they’re really precious, aren’t they. They’re expensive.

Joanna Ebenstein: Yes. I’ve never seen one for sale, and it wouldn’t have to be one of Clementi Susini’s 18th century ones that, there were 19th century iterations and they do float around from time to time. The other thing I’m considering is I have a friend who’s a waxworker who taught herself the antique methods, and I’m commissioning her to make one, I’ve a beautiful latrine that a skeleton lives in right now, and I think it would be a perfect place for a wax Venus. So, waxes in general are one of the things that are really close to my heart. When I think of what I’d like to acquire, it’s wax models. I don't know why: those, to me, are this perfect marriage of death and beauty, of real and idealized, of sex and death, all these things in one thing. So that would be the one thing I’d love.

Some of my favorite things in the Library right now, some of them aren’t even so beautiful, but I have this beautiful, to me, it’s like a little model it’s a folky looking model of a little man on a beastie, and I bought it in Korea, and it’s a Kokdu doll, and basically these are dolls that they would put on funeral biers, and the dolls would represent different spirits that would assist you in various ways on your journey through the underworld, your 42-day journey, and they might be musicians, they might be defenders, they might make you food, they might entertain you, and they were seen very much as embodying these souls, not even representing, but actually containing them, or being them, I suppose. And I found one of those at an antiques store. It’s not one of the things that people really notice in the space; there’s many more charismatic objects. I have a full-sized skeleton in the case which is what most people want to take a picture of; I have a two-headed duckling that my father gave me for my birthday that everybody wants to take a picture of. There are very charismatic things, but to me it’s the more subtle things, the Kokdu doll. I do have a leg moulage from the Deutsche Hygiene Museum workshop, which is one of my prized possessions.

You’ve probably met Eleanor Crook in London, or you know her. I took a class, she put the class on for me of moulage-making, and the piece I made in her class is actually one of my favorite things. She taught us how to make stubble and how to do color and certain hair, and it’s one of my favorite things.

Joanna Penn: That’s so cool. And I think this is what’s so great, because I live alocation-independent life, so I don’t collect objects, but I feel your fascination and I’m excited about the Anthology.

So tell us, what is the Anthology all about? Because I’m excited about that.

Joanna Ebenstein: Yes. The Anthology is kind of an incredible thing to me. For the longest time, for about five or six years now, I’ve been hosting these lectures in London and New York, and in other places, and my friend Colin Dickey, who wrote a book called “Cranioklepty” and another book called “Afterlives of the Saints,” I met him when I invited him to come speak at our space, and we became friends, he kept coming back, he’s from California but he lives here now. And one day, we were having lunch, and he said, “Look, I think there should be a book of some of these lectures, it’s such a shame, there are people all over the world who would like this material, and they’re ephemeral.”

And of course I’d thought of that before. My background is book design, my background is publishing, but to me there were certain insurmountable problems, like how do you pay for it, for example. How do you print it? I’ve never done these things before. And Colin basically came in, he said, “I think we should do it, and here’s how we’re going to do it, we’ll do this on Kickstarter and then duh-duh-duh,” and he was my perfect partner in this project. It would never, ever have happened without him. I would have thought about it, but never finished it. Because it’s, as you know, and I think when I met you, I was deeply immersed in it: it was a full year of hard work to get this thing done. That said, it’s kind of an incredible thing. I hope you’ll agree. I mean, it seems immodest to say, but it’s kind of, to me it’s like the blog, because we self-published and we raised enough money to make it a beautiful object, a covetable object, we were able to make this book exactly the book that I want, and I hope you will find that it’s the book you want, too.

So, it’s 500 pages, it’s 28 essays, full color throughout. The combination of the people within is, is really interesting as well: there’s people like Simon Chaplin, who’s the Head of the Wellcome Library, and Kate Forde, who’s curator at the Wellcome as well, from the exhibition I worked on with her about anatomical models. There’s a piece by our taxidermy teacher, which is kind of about the phenomenon of anthropomorphic taxidermy, there’s a piece from a bookbinder who lives in the neighborhood, he did a lecture on books bound in human skin. There’s pieces on everything from 19th century hysteria to spiritualism, to Frederik Ruysch, to 18th century anatomies, to anatomical models, to cabarets of death in fin de siècle Paris, to diableries, to even how you would want your body buried today and the idea of mourning.

So it’s very idiosyncratic; it’s the topics that people who read Morbid Anatomy will be well familiar with, but also what struck me when I was reading it and beginning to lay it out and to think about groupings is it’s much more than the sum of its parts, and when you read them together, it has become something very different, and certain themes that I never even suspected began to emerge, most notably this idea that’s summed up really beautifully in one of the first essays by Mel Gordon, which is about this old Memory Theater a Renaissance Memory Theater that no one really understands what it was. This idea of – and you might understand this as well from your own work – the siren call of the past, and yet that impossibility of ever knowing. And so all but one essay in this personified this in some way or another. This obsession, this obsessive need to time travel through scholarship, through art, and to try to access the mind of the past.

To me, I really, really felt that when I read these pieces, especially Mel’s, it was a, a thread that ran throughout that I never suspected was a thread in my own thought or my own interests until I saw the book that I curated, if that makes sense.

And so it’s really fun, and certain things just come up again and again, which was really interesting to me, like Walter Pater comes up in several, maybe four or five; Spitzner’s wax models comes up again and again; Frederik Ruysch comes up again and again. So there’s, there’s very literal themes that run throughout, and there’s very figurative themes, and I find it utterly fascinating and I can’t wait to see what other people think. I’m just so curious.

To me, it’s much like the blog and much like everything else that we’ve tried to do, or I’ve tried to do: I’m just trying to make the perfect thing for myself, and I have the faith that it will speak to others because of that. It is kind of a bizarre flowering, but it’s, to me, the perfect kind of bizarre flowering. It’s a beautiful thing that has a sense of humor but takes itself very seriously at the same time. The scholarship is real; the voices are different, some are scholarly, some are not, some are, some people are amazing writers, some are not, and I really wanted that mix, too. Colin and I both felt very strongly we wanted to keep the voices, and that’s one of the real strengths of the Morbid Anatomy lecture series, in my opinion, is it mixes what I would call rogue scholars with museologists, with artists, and all of these voices. Some are more skilled than others, but I like that, I want some to be more skilled than others. I like the texture and the difference and the democracy of it, if that makes sense.

Joanna Penn: I love your live events. Obviously, you’re in America right now and I’m in London, and I came along to one at the Old Operating Theatre, and it was death drawing, so the model actually was an Anatomical Venus, and actually that came out in my book as a stripper at the Torture Garden, I don’t know if you know of the Torture Garden?

Joanna Ebenstein: No, I didn’t know that.

Joanna Penn: Yeah, but seeing her standing there, naked but painted as the Anatomical Venus, that was kind of awesome. So I wanted to ask you, because I think that the challenge I have is people say to me, “Well, aren’t you writing horror: the stuff you’re talking about, doesn’t that fall in the horror camp?” But I don't find that, that event to me, there was nothing horrific, and you talk about academics there: these are not kind of horror events are they.

So, how do you class the events you do?

Joanna Ebenstein: Oh, to me, events like writing or blogging, it’s like a form of inquiry; it’s about learning things, and it’s about learning things with pleasure. And I think part of the reason people start to try to push it into saying it’s horror or this or that, or sub-cultural, is that, again, this is an edge people aren’t comfortable with, this edge of spectacle and pleasure with learning. And part of what I’m trying to do through Morbid Anatomy, and what I want to do through the Museum, and what I want to continue to encourage other museums to do, is not to throw the baby out with the bathwater, as it were. Not to discard the idea of seduction and pleasure.

I think there’s a lot of distrust of pleasure, and pleasure is how you entice people to learn, in my opinion. And I think about that with the blog a lot. My blog is image-driven: I won’t do a post unless there’s a strong image, because, first of all, I’m an artist, so I’m a visual person, but also because I think you have to give someone a reason to read, and an image is the seduction that then makes them want to learn.

So I think what confuses people at events like that is that it’s both popular and scholarly, and that’s a division in our culture that has been encouraged by academia too –to its detriment, in my opinion. I feel like what I’ve tried to do is discover these academics, like that night, we had John Troyer and Anna Maerker, who are academics who really get it, who are fun and interesting and actually want to communicate their material to a popular audience. Many academics don’t think that’s very important, and don’t know how to, even if they did. So these are the kind of people I try to bring into our community, people who really know their stuff and really can tell a good story, or at least want to engage on a popular level.

But I think that it confuses people: again, it’s these edges of what we consider appropriate for scholarship. And when you complicate that, when you throw in some naked woman dressed as an Anatomical Venus, again, it starts to flicker on an edge, and people just don’t know what to make of it exactly. They get confused and then just step away.

Joanna Penn: Which is so fascinating, because there was nothing sexual about her, and nothing horrific either. It was fascinating, I’ve never done life drawing, either, I wasn’t very good at it, to be honest!

Joanna Ebenstein: First time, nobody is!

Joanna Penn: But it was great. So, so moving on, the Museum. This is very cool, I’m an active person in the Kickstarter, I’m very excited about this.

Joanna Ebenstein: Thank you very much.

Joanna Penn: Tell us about this Kickstarter project and the Museum.

Joanna Ebenstein: So, for the last six years, I’ve been running what I call the Morbid Memory Library and Cabinet, and it’s about 300 square foot, basically a walk-in closet that I’ve been bringing people in and making my collection available. Last year, right before I left for London, as a matter of fact, I met these two wonderful people, these identical twins, as it turned out, who came to my space, and one of them said, “You know, there should be a gift shop/ café like this,” and I said, “There should be, and I could build you a great museum to go with this, and it should happen right now.” And I didn’t realize that these were people who just get things done, so before I knew it, they were looking at property and things were being planned, and when I came back from London in September, this is what I’ve been doing full time ever since.

So, we found a space. We’re moving from this 300 square foot tiny room with no light to a 4,200 square foot former nightclub, actually, with roof access, and it’s going to be pretty epic and bizarre. It will be like the museum form of the book: it’s kind of a bizarre flowering, we’re making it exactly how we think it should be.

The basement floor, the cellar, will be where we have our lectures and workshops, kind of like what I was doing in London, but we’ll be able to seat 65 people, so we can really accommodate much larger crowds. The ground floor will be a gift shop, café and ultimately a bar when we get a liquor license, and the top floor, it’s divided into two. One third of that is the Morbid Anatomy Library and Permanent Collection, and the other part is a temporary exhibition space. Our first exhibition will be devoted to the art of mourning, and will have lots of other things about the topics that are explored on the blog.

Joanna Penn: Awesome. I think it we definitely need one. And I want it in London, you know!

Joanna Ebenstein: Oh, don’t worry, that is planned, too. I am so into starting one in London. But, the thing about London is you guys have things that we don’t have here. I mean, you have an embarrassment of riches in London, you have the Wellcome, you have the Hunterian. We have nothing. That’s the thing: I’m the only game in town when it comes to this material, because New York is a city of commerce, and all of the interesting, quirky museums pretty much get pushed out. Like London, it’s quite expensive to operate here. But we don’t have this tradition of old medical museums and an appreciation of history that keeps them from being thrown away.

So, we do have the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, which is an hour and a half or two hours from here, but in New York, there’s nothing like this. So we’re really, really needed here. But honestly, London is my favorite place in the world, and if I could start a branch there, I would be there in a second. That is our plan.

Joanna Penn: You never know, I might put my hand up to help with that!

Joanna Ebenstein: Excellent, you’re hired!

Joanna Penn: Fantastic. So, people can just find that on Kickstarter by searching Morbid Anatomy.

Joanna Ebenstein: Absolutely: Kickstarter, Morbid Anatomy will bring you right there.

Joanna Penn: Brilliant. And where can people find the blog as well?

Joanna Ebenstein: The blog is at http://morbidanatomy.blogspot.com.

Joanna Penn: Or just put in Morbid Anatomy.

Joanna Ebenstein: Yes, it’s the first thing that comes up, for sure.

Joanna Penn: Ut is. And the book, is that available everywhere, or just on the blog?

Joanna Ebenstein: The book is available in a number of places. The cheapest place to get it right now is to get it through the Kickstarter. So if you go to the Kickstarter, for a $25 donation to our Kickstarter, you get a copy of the book with the shipping included, if you’re in the US, $35 if you’re in Europe, in England or anything. So, that is by far the cheapest way to get it. If you go to the Kickstarter, make a $25 donation, add 10 if you’re from England, you get a copy of the book.

Joanna Penn: Cool: that is a brilliant deal!

Joanna Ebenstein: Thank you, we tried.

Joanna Penn: So thanks so much for your time, Joanna – that was brilliant.

Joanna Ebenstein: Thank you so much, and it was a pleasure talking.