Conspiracy theories are not exactly new. Humans just love coming up with strange – or suspicious – explanations for unusual behaviour. But The Da Vinci Code definitely popularised the idea that codes and secrets could be hidden in works of art.

And where better to hide a secret than in plain sight? Only the initiated can understand it and decode the message.

Even if you’re not sure that the figure in Da Vinci’s The Last Supper is Mary Magdalene, here are some other artistic conspiracy theories that you might find more plausible!

Michelangelo immortalised Mary Magdalene in marble, not the Virgin Mary

Michelangelo's Pieta depicts the crucified body of Jesus lying in the arms of the Virgin Mary. It's one of the most famous sculptures in the history of art.

But commentators aren't exactly buying it. After all, Jesus was 33 when he died – but Mary doesn't look much older. That’s not exactly surprising. After all, the Virgin Mary is nearly always represented in an idealised way.

Art historian Cinzia Chiari put forward a different theory in the Biblical Conspiracies series. For her, the statue is indeed of Mary. Only not the Virgin Mary. No, the Mary in the sculpture could be Mary Magdalene.

Is Michelangelo saying that Mary Magdalene was Jesus' lover?

Possibly. Or maybe he's just returning Mary Magdalene to her place in history. After all, she was present at the crucifixion. According to the gospel of John, Mary was also the first to discover Jesus had left his tomb. The Pieta might mark Michelangelo’s attempt to depict her sadness at his death.

But the discovery of a terracotta model in 2010 shows that Cupid was originally supposed to be in the scene too. It can’t be confirmed that the model was made by Michelangelo, but experts are convinced that only he would be brazen enough to put a Greek god in a sculpture intended for the Vatican.

But as Cupid was the god of romantic love, it makes more sense that he'd appear in a scene between Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

Michelangelo also thumbed his nose at the church – in the Sistine Chapel

One of Michelangelo's greatest works is his Sistine Chapel painting. It tells the story of the Book of Genesis.

But its success rests on a slightly morbid part of Michelangelo's past. At the age of 17, he started dissecting corpses to better understand human anatomy. It's unclear if he was given them, or he dug them up. The latter would make him a more famous bodysnatcher than Burke and Hare.

But Michelangelo wasn't looking to sell the bodies. He just wanted to make anatomical sketches. And some of these are hidden within his Sistine Chapel paintings.

In 1990, physician Frank Meshberger spotted an anatomical illustration of the human brain in cross section. Michelangelo hid it inside the God Creating Adam central panel.

But in 2010, Ian Suk and Rafael Tamargo also found precise illustrations of the spinal cord and brain stem within The Separation of Light from Darkness. The brain stem even forms God's throat!

Experts are unsure if the hidden illustrations were intentional, but artistic conspiracy theories exist about their possible meaning. Michelangelo grew disenchanted with the Church – believing instead in the possibility of direct communication with God.

And with the Church's denunciation of science, was Michelangelo making fun of their stance? Or is it just another of art’s strange conspiracy theories?

British artist Walter Sickert was Jack the Ripper – and he painted scenes of his murders

The identity of Jack the Ripper is probably one of the most hotly contested debates of the last 128 years. It seems that everyone from Prince Albert to Richard Mansfield was accused of being one of history’s most notorious serial killers.

Most famous for painting both nudes and nightlife scenes, Sickert captured the dancers and lower orders of London. Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec did much the same in Paris.

And it’s these paintings that provide the ‘evidence', particularly a series of grim paintings created in 1908. Known as The Camden Town Murder, they were inspired by the murder of a prostitute in the Camden area.

Cornwell claims the paintings are too similar to the autopsy photos of the Ripper's victims to be a coincidence. She even had one of them torn up, looking for evidence.

DNA samples were taken from both the letters allegedly written by the Ripper and those written by Sickert. There were no matches, though Cornwell was triumphant when two of the letters had the same unusual watermark.

Given Sickert's father was a stationer, it's fair to assume he supplied a lot of people with paper.

Cornwell herself admits it’s nigh-on impossible to know for certain who Jack the Ripper was. She maintains it was Walter Sickert…but the rest of the art world disagrees.

The Mona Lisa contains a hidden code in her eyes

But is the figure actually a man – or even Da Vinci himself? And where exactly is the painting set?

Stranger still, Italy’s National Committee for Cultural Heritage claimed that a secret message was embedded in the painting. According to them, Da Vinci put tiny numbers and letters into the eyes.

Now, such letters can only be seen by magnifying high-resolution images of the painting. They're invisible to the naked eye. Apparently ‘LV’ appears in the right eye, while the figures in the left eye are harder to understand.

But experts agree that the letters are difficult to read clearly. So did Da Vinci foresee the development of magnification technology? Or are people just seeing what they want to see?

Conspiracy theorists note that da Vinci took the painting everywhere with him in his later life. Was he protecting a secret message? Or just protective of his final image of his mother?

The Last Supper hides a musical secret

Da Vinci’s The Last Supper was critical to the plot of The Da Vinci Code. And like the Mona Lisa, the painting apparently hides secrets beyond the identity of the figures. In this case, a musical score.

This secret doesn't hinge on the figures – but the bread rolls on the table.

In 2007, computer technician Giovanni Maria Pala noticed the placement of the rolls looked like musical notes. He drew a musical staff across the painting to find out what the notes were.

Played left to right, the music makes little sense. But Da Vinci always wrote right to left. Following that logic, the loaves (and the hands of the Apostles) become a 40-second musical score.

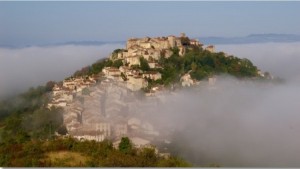

Alessandro Vezzosi, director of the Da Vinci museum in Tuscany, admitted that Da Vinci was also a musician. The spaces in the painting provide the proof that the rolls and hands were intended to act as musical notes. Even detractors note the music is too perfect to be a simple coincidence.

Rembrandt and Vermeer traced their masterpieces

Tracing images is a tool beloved of artists and designers when they want to save time. Adobe Illustrator even includes an Image Trace option if you want to turn a scanned image into a vector graphic. But could two of history’s most realistic painters have traced their famous works?

The term ‘camera obscura’ appeared in 1604. It describes a device that projects real life images onto nearby surfaces. We'd recognise it today as an early type of camera.

But David Hockney thinks that 17th-century artists like Rembrandt and Vermeer used similar devices to create the basis of their lifelike paintings.

Hockney came up with his theory after comparing the projection-trace drawings of Andy Warhol with 19th-century drawings by Jean-Dominique Ingres. The parallels got him thinking – could other artists have traced their masterpieces from real life?

The art establishment deplored Hockney’s conclusion, but researcher Tim Jenison teamed up with Penn and Teller to see if it could be done. They built a set to match Vermeer's The Music Lesson and set up a camera obscura.

No one can say one way or the other if Vermeer and Rembrandt were even aware of the camera obscura at the time. But the results seem to speak for themselves…

Francisco Goya didn’t paint his infamous Black paintings

If you’re looking for the best representations of nightmares on canvas, then Francisco Goya is a good place to start. Or is he?

The Spanish artist Goya was originally known for traditional portraits or war scenes.

But he suffered a serious illness in 1819. After his recovery, he decorated the walls in two rooms with dark, nightmarish visions. The paintings would become the Black Paintings, now in the Museo del Prado.

In the traditional story, Goya signed the house over to his grandson, Mariano, in 1823. The following year he moved to France. Mariano apparently only discovered the paintings after Goya died.

Art historian Juan Jose Junquera doesn't buy that explanation. After all, Goya still received visitors while he was in the house. But no one ever reported seeing the paintings – and you can't exactly miss them.

Only one inventory of the house ever mentions the paintings. Published in 1928, the authors claim it was written in the 1820s. But Junquera believes it’s a fake, because it uses contemporary descriptions of objects rather than early 19th century words.

Even more strange, the original bill of sale of the house describes a one-storey dwelling. The upper storey was added in 1830. The Black Paintings were found on both the house's upper and ground floors…but the upper level was added two years after Goya's death.

Instead, Goya expert Juliet Wilson-Bareau pointed to Goya's son, Javier, as the real creator of the paintings.

Javier could paint, and he knew his father’s techniques well. But he'd never made money as an artist. What better opportunity than the death of his mentally unstable father to finally sell his work?

A painting of Elizabethan magician John Dee had skulls removed

John Dee, the Tudor scientist and occultist, appears in an intriguing Victorian painting by Henry Gillard Glindoni. In it, Dee performs an experiment for Elizabeth I and her court.

But that's not the weird part. X-rays have revealed that a ring of human skulls originally encircled Dee. The ghoulish secret was painted over.

Most experts think the changes were to make the painting more palatable to buyers. But the conspiracy theories say otherwise. While Dee is now known as more of a scientist, in his lifetime he was something of a conjurer.

What we call science now was closer to ‘natural philosophy’ in Dee’s day – and considered more like magic.

Exhibition curator Katie Birkwood believes the editing trick was to help cement a more serious and stately reputation for Dee. But last year, the Royal College of Physicians ran at an exhibition about John Dee's lost library. And it included his crystal ball and an obsidian mirror.

Perhaps Dee was more of a magician after all…

Vincent Van Gogh may have created his own homage to The Last Supper.

The Cafe Terrace at Night (1888) shows an evening scene of diners at a cafe. They're enjoying the night air while a waiter moves between them.

But Jared Baxter thinks it is Vincent Van Gogh’s homage to The Last Supper. The waiter seems to have long hair, and his white uniform resembles Jesus’ white tunic. Crucially, twelve diners sit at the tables around him. There's also a shadowy figure exiting stage left. Taken together, Baxter thinks the composition echoes Da Vinci's.

It sounds like another of the far-fetched conspiracy theories. That’s until you discover that at the time he painted it, Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo about the work, explaining that he had a “tremendous need for, shall I say the word—for religion.”

There's even a large cross in the painting, in the window behind the waiter/Jesus.

Perhaps the troubled artist wanted to explore the security of religion. Or maybe he just wanted to reference the work of a master painter. You can decide for yourself!

Do you know any other artistic conspiracy theories?

All of these conspiracy theories rest on hidden meanings or codes. Perhaps we’ve all been fooled into thinking they’re more than just awe-inspiring works of art.

Or maybe the conspiracy theories are true. But next time you’re passing an art gallery, try taking a look at their permanent collection. Who knows what you’ll find hidden in the oil or marble?