I love John Connolly's Charlie Parker series, and its blend of crime and the supernatural was the major influence for my London Psychic trilogy. I met John in person at Crime in the Court in London (at left). I'm a total fan-girl 🙂 I also interviewed John for The Big Thrill July 2015 edition, and include the interview below.

I love John Connolly's Charlie Parker series, and its blend of crime and the supernatural was the major influence for my London Psychic trilogy. I met John in person at Crime in the Court in London (at left). I'm a total fan-girl 🙂 I also interviewed John for The Big Thrill July 2015 edition, and include the interview below.

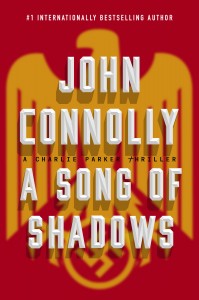

John Connolly is the bestselling author of the Charlie Parker mysteries, the Samuel Johnson novels for middle-grade readers, and co-author of the Chronicles of the Invaders plus other works.

His latest book, A SONG OF SHADOWS, is the thirteenth book in the Charlie Parker mystery series.

Your latest book, A SONG OF SHADOWS, weaves European history into a string of murders in Maine, all while Charlie Parker recovers from devastating injuries.

How much of the story is based on historical truth? Why did this particular aspect of Nazi history interest you?

My eye had simply been caught by the ongoing attempts of the United States to extradite an alleged former Nazi named Hans Breyer to Europe to face war crimes charges. (Breyer died last year just before he could be extradited.) I began to wonder how many of these men and women were left, and how seriously the hunt for them was being taken.

Out of that research came a lot of surprising details about just how little energy the Allies invested in bringing these people to trial, and how the British and American authorities protected them, mainly in order to milk them for intelligence about the Soviets. I found it fascinating, and just hoped that readers would find it fascinating too.

It then turned out to be very topical because just as the book came out Oskar Gröning, the “bookkeeper of Auschwitz,” went on trial, and I suppose that the seventieth anniversary of the liberation of the concentration camps also reminded people of what had taken place in them.

I suppose I was also aware that it’s really hard to find anything new to say about the Nazis and the Holocaust, so in that sense I was a bit reluctant to take on the subject. Yet those old men and women nagged at me, and their cases found a resonance in one of the recurring questions in the Parker books: are we defined only by the wrongs that we do, and are some wrongs so terrible that they cannot be forgiven?

All the Charlie Parker books have a supernatural edge, which is what keeps me as a reader coming back. Where do your ideas about the supernatural come from? How do they fit with your own beliefs?

The supernatural elements in the books drew the greatest amount of criticism early in my career, and they still make the more conservative elements in the genre uneasy. I like the fact that Americans call crime novels “mysteries,” and the roots of the word “mystery” are themselves supernatural. A mystery was a truth that could only be revealed through divine revelation.

In a similar vein, I’ve always liked William Gaddis’s quotation from the novel JR: “You get justice in the next world, in this world, you have the law.” But mystery fiction has always been uneasy about the difference between law and justice. It does not accept that justice should be left for the next world, and that we should be content with imperfect legal systems in this one. If you take Gaddis’s view to the extreme, it implies the existence of both a moral universe and an entity governing it that is capable of dispensing justice. If we call that entity “God,” then there may also be a “Not-God.”

So I suppose the Parker novels take this idea and run with it: notions of justice, of morality, of retribution, and of redemption. I keep coming back to that word because if, like me, you come from a Judaeo-Christian background—I’m a bad Catholic—then “redemption” comes freighted with a certain spiritual baggage.

Your “good guys,” Charlie, Louis and Angel, might be perceived as “bad” in many ways. But the bad guys are always worse. How do the notions of good and evil fit into your characters? Can even the worst of them be redeemed?

I don’t think Parker, Louis and Angel are “bad.” As is remarked in one of the novels, they’re on the side of the angels, even if the angels aren’t sure that this is an entirely positive development. They are prepared to compromise themselves morally to achieve certain ends, and Parker in particular is aware of the potential cost of such compromises, but it comes back to that earlier question: are we defined only by actions that might be perceived as negative, or how bad do such actions have to be before they define us in that way?

I don’t believe that most people are evil. Selfish, yes. Fearful. Angry. Deluded. All those may result in evil acts being committed, but very few people set out actively to do evil. As someone once said, everyone has his reasons. For me, the use of terms like “evil” or “monster” is, for the most part, the equivalent of shrugging one’s shoulders and walking away. It’s a failure, or an unwillingness, to attempt to understand, and without understanding there can be no change. But the books do suggest that very, very occasionally, we may encounter acts or individuals so depraved as to suggest a deeper, darker well is being drawn upon.

The Charlie Parker books are set in the U.S., but you’re Irish and live in Dublin. How does Ireland emerge in your writing, even if it’s camouflaged?

I suspect it emerges through a fascination with folklore and the uncanny, and a comfort with letting rationalism—which is the basis of detective fiction—blend into anti-rationalism, which is the basis of supernatural fiction. I see them as complementary, rather than the antithesis of each other. I think, too, that the process of hybridization interests me, the possibility of creating or enhancing new sub-genres.

You’ve said that writers are like magpies, picking out interesting things from the world and storing them up for stories. What’s fascinating you at the moment?

Well, I’m writing the next Parker book, and I want it to have a strong folkloric element, but I may have to invent my own piece of folklore for it to work. Then again, isn’t that what folklore is about? We imagine, we create, and it becomes part of an ongoing tale. I’m always quite pleased when someone reads my books and has trouble spotting what’s real, and what’s made up. When that happens, I like to think that I’ve done my job right.

You can find A Song of Shadows and all the other Charlie Parker books on Amazon and all bookstores.